(RNS) — When Cait West got on a plane and left behind the Christian patriarchy movement at age 25, she hoped for a clean break.

But years of covering up her body, constantly fearing eternal damnation, being isolated from the outside world and being raised to take over society for God weren’t easy to shake.

“I wanted to focus on fiction writing, but my own story just felt like it was trapped inside of me and I needed to get it out,” West told Religion News Service in a recent video interview.

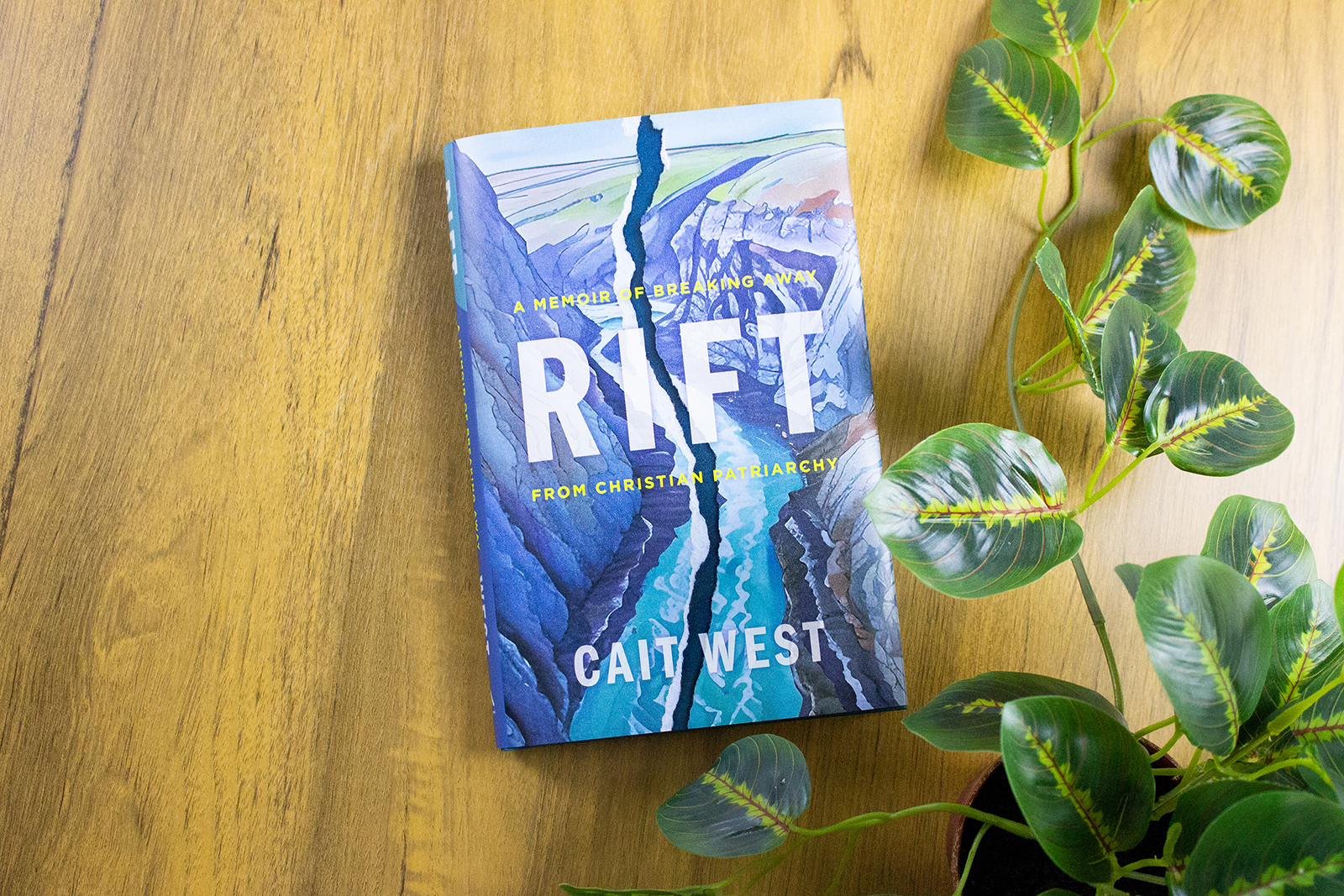

On Tuesday (April 30), that story will be released in the form of her new book, “Rift: A Memoir of Breaking Away From Christian Patriarchy.” Written primarily with other abuse survivors in mind, West’s story is one of navigating a life deprived of agency, surviving complex trauma, embracing her freedom and making space for the fullness of herself. RNS spoke to West about her decision to leave her religious community, her courtship experience and her discovery that patriarchy isn’t all that fringe. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

What do you mean when you refer to the Christian patriarchy movement?

Cait West. (Photo by Teri Genovese)

The Christian patriarchy movement was in full force in the ’90s and the early 2000s. It’s related to Quiverfull ideology — Bill Gothard, Vision Forum, the Duggars. And it’s very connected through the homeschooling community. God is the ultimate patriarch, and men are his representatives on Earth. The wife submits to him, and children submit to their parents. Growing up, I was told I would become a wife and a mother. All my education was pointed toward how to help my future husband, and when I turned 18, I wasn’t allowed to go to college. I couldn’t get a real job outside of the home and I couldn’t go on dates. I was told I would be a child until I got married. I didn’t have a driver’s license or any access to the outside world. I couldn’t decide what my future would look like. I had to follow my dad’s rules for courtship and wait for him to find me a husband. That’s why they called me a stay-at-home daughter.

At what point did you begin to question this religious framework?

I saw my older sister get married through the courtship process, and then struggle with an abusive marriage. They said if we followed these rules, we’d end up happily married. But that doesn’t always happen. I locked that piece of information away. I had my first courtship when I was 20. My father mediated all our main conversations, so I didn’t really get to know him personally. But I thought I was going to marry this person, and then my father ended the courtship because he didn’t think he was the right person. I had no say and I was devastated. My father told me it was sinful to for me to be heartbroken and to feel affection for this person. Something inside me said that’s a lie, it can’t be true that my feelings are sinful. That’s when I started to wake up to my reality.

How did your experience with courtship shape the way you came to view love and intimacy?

From before I hit puberty, I was told I wasn’t supposed to fall in love until I was betrothed. I’m somewhat of a hopeless romantic, but I had to repress that side of me because that was not allowed.

When I had that first courtship, it changed how I stood up for myself, because I realized my father could just keep me at home forever if he decided to. And so I decided if I fell in love with somebody else, I wouldn’t let my father stop me from having a relationship. And that’s what happened. I had a second courtship, but my father ended that after a week. We continued to have a relationship outside of his permission, and that’s the person I eventually moved out to get married to. And so that is the big rift in my book, where I’m leaving my family. At that point, I was throwing all the rules out the window about what relationships should look like. I realized I didn’t have a good example in my parents’ marriage, I didn’t think that courtship worked very well, and I just wanted to be with the person I loved.

What ultimately led you to move on from church altogether?

When I left my family, I wanted to hold on to the religion I had been brought up in. I came to believe that what my father was saying was not who God was, and I went to church for quite a few years. But over time I saw red flags. The church was complementarian, when men and women are seen as having different roles of equal value. It seemed clear to me it was still patriarchal, because all the leadership positions were held by men. At one point, I wanted to write resources for the church about spiritual abuse, and they asked me to get my husband’s permission. A new associate pastor started sharing books by patriarchal leader Doug Wilson, and when I brought up my concerns, nobody seemed to think it mattered. The senior pastor told me adults could discern for themselves. With the Trump presidency, I saw an increase in Christian nationalism in the church, and I started getting panic attacks in church again. I realized, this isn’t a good place for me. I tried to make changes and speak up, but it didn’t seem like anyone really wanted to receive that, and so I eventually left.

“Rift: A Memoir of Breaking Away From Christian Patriarchy” by Cait West. (Courtesy image)

How do you think about spirituality these days?

I stopped believing in a patriarchal God first, and then I stopped believing in a wrathful God. And then I started just questioning, is there a God? When people push me to pick a label, I usually say agnostic because I feel open to the idea that I don’t know everything. But I do believe there is something that connects all of us humans together. And I know that, for me, the closest I’ve experienced a higher power is when people unconditionally love each other. To me, that’s more important than choosing doctrine over people.

Can you discuss the geological or ecological interludes interspersed throughout the book?

I knew from the beginning I didn’t want to write a book that just told my story chronologically. My memories aren’t chronological, and I think that’s common for people who have experienced trauma. I’m fascinated by braided narratives, where several different storylines are woven together to create a new meaning. Throughout the whole book, I include the geological story of all the places I’ve lived. Part of that is to provide a bigger metaphor to explain how I feel about what happened. It was also a grounding practice to write about geology, the cosmos, and compare it to my little life.

How do you see your experience of growing up in the Christian patriarchy movement in relation to the broader Christian landscape?

I used to feel like my family’s way of life was very fringe. But now that I’m out, I see patriarchy in many churches in the U.S., just in different flavors. When it’s subtle, it can be more problematic, because it’s not easy to directly address. But the extreme still exists, stay-at-home daughters still exist. It just doesn’t use the same terminology.

Also, spiritual abuse and emotional abuse can happen in any community, including liberal churches. It is easy to point fingers at the extremes and not look at yourself, but I would hope people can take stories like mine and examine how this might be happening in their own communities in different ways.